Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome is a rare progressive inflammatory condition that presents with bilateral granulomatous panuveitis and a constellation of neurologic, auditory, and integumentary manifestations. The name of the syndrome is taken after Alfred Vogt, a Swiss physician who described the first case in the literature, and Japanese researchers Yoshizo Koyanagi and Einosuke Harada who comprehensively described the syndrome and its clinical course in the early twentieth century (1).

Early ocular manifestations of VKH include multi-focal serous retinal detachments (SRDs) and choroidal thickening, which later develop into granulomatous anterior uveitis and progressive posterior segment depigmentation, also known as “sunset glow fundus”. Systemic manifestations range from nonspecific symptoms resembling a viral illness during the initial onset to hearing loss, poliosis, vitiligo, and alopecia in the chronic stage (2). VKH can occur at any age but the onset is typically in the middle-age, and appears to affect women slightly more than men (3). It is highly prevalent in Asians, accounting for 7% of all ocular inflammatory conditions in Japan and 15.9% in China, but has been reported less frequently in Caucasians or blacks (4-6).

The diagnosis for VKH is challenging due to ocular and extraocular manifestations that occur at different stages of the disease and a broad differential, which includes infectious and noninfectious uveitis (NIU), intraocular lymphoma, and rare conditions like sympathetic ophthalmia (SO). The evolution of the diagnostic criteria over the last few decades reflects our growing understanding of the clinical features and disease progress of VKH (7-9). The pathogenesis of VKH is still not known, but there is evidence that it involves a T-cell mediated immune response against antigens on melanocytes in genetically susceptible individuals, such as those with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) subtype DR4/DRB1*04 (10).

The convalescent stage occurs several weeks after the onset of acute uveitis stage and is characterized by depigmentation of the fundus, or “sunset glow fundus.” This feature is less frequently reported in Caucasians, perhaps due to challenges discerning features of depigmentation against a less pigmented fundus (13). Interestingly, a study found higher levels of pleocytosis in patients who eventually developed sunset glow fundus, which suggests an association between the severity of inflammation with developing chronic signs of VKH (14). Nummular chorioretinal scars are also common in the late stage of VKH and were reported in over 75% of patients who were examined several weeks after disease onset (15). Another form of depigmentation that is seen in the early chronic stage is perilimbal vitiligo, or “Sugiura’s sign”, found in up to 85% of Japanese patients with VKH but less frequently in studies without a predominant have Japanese cohort (2,13,16).

The chronic recurrent stage is characterized by subclinical or recurrent episodes of granulomatous anterior uveitis and is associated with complications from chronic intraocular inflammation. The most common complications of chronic VKH include cataracts, possibly due to prolonged systemic corticosteroid therapy, followed by glaucoma, and subretinal fibrosis (17). Sunset glow fundus remains a distinguishing feature of chronic VKH, reported in 68% of Japanese patients with ocular inflammation lasting for more than 6 months (14). Overall, the intraocular inflammation in VKH follows a predictable course that starts with a predominantly posterior uveitis and evolves into an anterior granulomatous uveitis during the chronic stage (18).

Extraocular manifestations in VKH follow a less predictable course and can variably affect the auditory, integumentary, and neurologic systems, typically in the late stage of VKH. The most common systemic manifestations include headaches and tinnitus, reported in 49% and 36% of patients with VKH, respectively (13). Systemic manifestations in VKH have also been reported to vary in different populations. Native American patients with VKH reported significantly less frequent systemic symptoms compared to non-Native Americans, but integumentary manifestations like vitiligo were more common (19). Hispanic patients with VKH also have fewer systemic manifestations, including tinnitus, which was reported in 10–15% of patients (2,20).

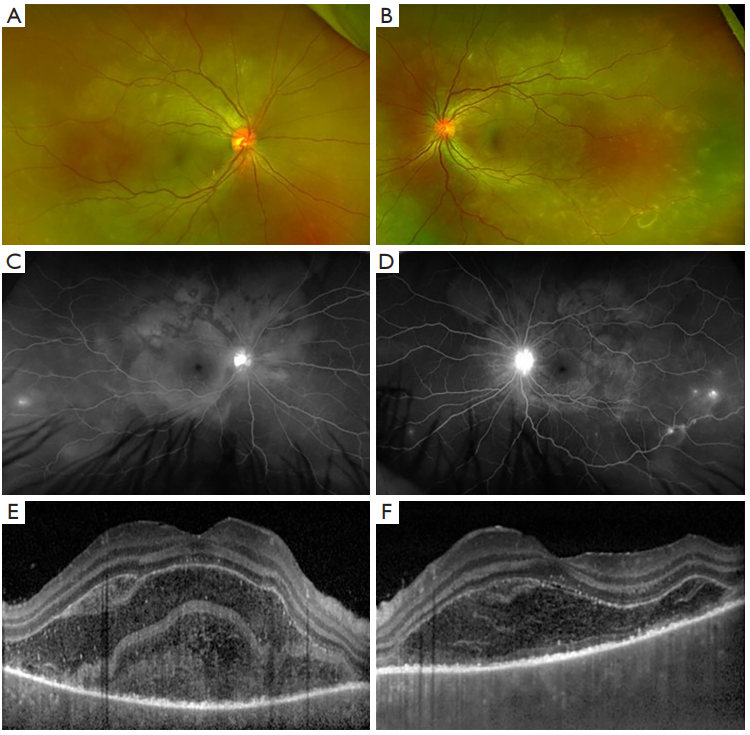

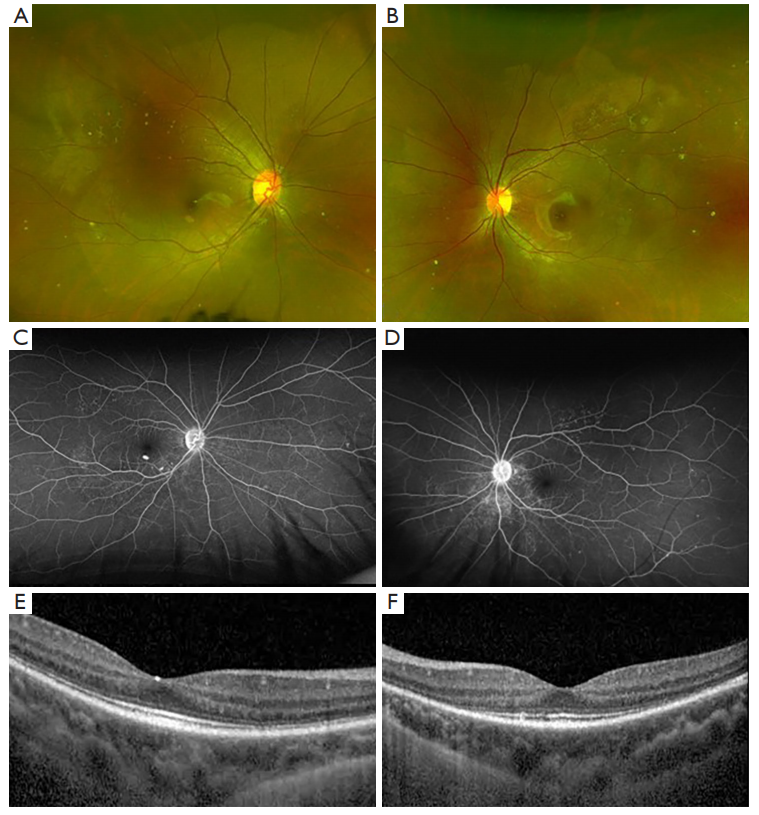

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) can be used to visualize and monitor the SRDs and subretinal fluid in patients with acute VKH (24). A distinguishing feature of SRD in VKH is the multiple cystic space that is separated by hyperreflective septa, which has been hypothesized as inflammatory fibrinous material due to its disappearance with corticosteroid treatment (25,26). In a recent study, this fibrinous membrane was found in 61.5% of eyes in patients with initial-onset VKH and was associated with younger age and shorter time from the onset of symptoms, which suggests that it is an early feature of SRD in patients with acute VKH (27).

Swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) is the latest generation of OCT imaging that has a faster scanning speed and uses a longer wavelength than conventional SD-OCT imaging, resulting in better visualization of the deeper layers of the retina and choroid. Recently, Agarwal and colleagues used SS-OCT to evaluate 62 patients with acute VKH and found that 95% of eyes with SRD had a split at the photoreceptor myoid, leaving behind a bacillary layer consisting of the remaining myoid, ellipsoid zone (EZ) and interdigitation zone (IZ) (28). This is called “bacillary layer detachment” and has been described in SRD associated with toxoplasma retinochoroiditis, tubercular choroidal granuloma, and other inflammatory diseases (29,30).

Enhanced depth imaging (EDI) is a method of SD-OCT that can visualize the deeper structures of the eye and has been used to characterize the choroid in the acute and chronic stages of VKH (31). Thickened choroid on EDI-OCT is a common feature of acute VKH and was incorporated into the diagnostic criteria that was recently developed by Yang and colleagues (8). On the other hand, the thickness of the choroid in patients with convalescent VKH is comparable to that of control subjects, which is likely a result of ongoing inflammation and loss of choroidal structure (32). In a study by Nakayama and colleagues, EDI-OCT detected rebound choroidal thickening in patients during corticosteroid tapering in the absence of clinical recurrence (33). Subclinical inflammation can go unnoticed in patients with VKH, which can lead to chronic disease and irreversible loss of visual acuity. EDI-OCT is a quick and noninvasive imaging test that can be used to monitor the disease status and treatment response in patients presenting with thickened choroid in the acute stage of VKH.

FA findings in VKH have been well described in the literature. In the acute stage, optic disc hyperfluorescence and early pinpoint areas of hyperfluorescence followed by late pooling in SRD can be seen on FA (Figure 1C,1D). In the chronic stage, common findings include optic disc hyperfluorescence and spotted hyper and hypofluorescence, or “salt and pepper” fundus appearance, representing RPE damage (34). SRD in VKH appears as multi-lobular pooling of dye within the subretinal space on late-phase FA (26). In patients with acute VKH but without SRD, delayed choroidal perfusion, optic disc hyperfluorescence, mild pinpoint leakage, and choroidal folds can be seen on the FA (24).

ICGA provides enhanced visualization of the choroidal circulation and can detect subtle choroidal inflammation that is not detected by FA. Herbort and colleagues identified major ICGA signs in patients with acute VKH, including early choroidal stromal vessel hyperfluorescence and leakage, hypofluorescent dark dots, fuzzy vascular pattern of large stromal vessels, and disc hyperfluorescence. Of these, hypofluorescent dark dots, representing choroidal inflammation, were the most prominent and resolved in a majority of patients who underwent treatment (35). In another study, the hypofluorescent dark dots resolved with high-dose but not medium-dose corticosteroids in patients with clinical improvement of VKH (36). ICGA-guided therapy has been shown to prevent progression to chronic disease in a small number of patients who were managed more aggressively based on subtle findings of choroidal recurrence on ICGA (37). Interestingly, a study by Chee and colleagues found early pinpoint peripapillary hyperfluorescence on the FA was associated with a good prognosis in patients, whereas ICGA findings did not have prognostic value (38).

The diagnostic criteria for VKH syndrome have been modified several times in the last few decades. In 1978, Sugiura published a set of criteria for the diagnosis of VKH, which requires (I) acute bilateral uveitis, (II) retinal edema with typical FA findings, and (III) pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) noted in early stage of the disease. The diagnostic criteria did not consider any other systemic manifestations involving the auditory or integumentary system and excluded a significant proportion of patients with VKH who did not have CSF pleocytosis, which is a common but not universal finding in patients with VKH (39).

The diagnostic criteria by the American Uveitis Society (AUS), also published in 1978, added a criterion to differentiate VKH syndrome from SO, which can present with similar findings on exam and imaging. In addition, at least one finding from three of the following categories is required: (I) bilateral chronic iridocyclitis; (II) posterior uveitis; (III) neurologic signs; and (IV) cutaneous signs. A major criticism of the AUS diagnostic criteria is the lack of consideration of the different stages of VKH, since posterior uveitis occurs in the acute stage while iridocyclitis and systemic manifestations are more common in the chronic stage of VKH.

In 2001, the revised diagnostic criteria were published by experts after the First International Workshop on VKH in 1999. The criteria categorize VKH into complete, incomplete, and probable VKH according to the number of systems involved. The ocular manifestations are differentiated according to the stage of the disease and incorporate findings from FA and ultrasonography. The revised diagnostic criteria have been reported to capture 90% of patients diagnosed with VKH with Sugiura’s criteria and 100% of patients who were diagnosed with VKH based on the clinicians’ expertise (15,39). In a study evaluating the revised diagnostic criteria, Kitamura and colleagues reported two patients with bilateral disc edema, inflammatory cells in the AC, and CSF pleocytosis, who were not diagnosed with VKH due to the absence of SRD. The presence of focal subretinal fluid or SRD is central to the diagnosis of early VKH in the revised diagnostic criteria, since without either, characteristic findings must be present in both FA and ultrasonography for the diagnosis of VKH. Yamaki and colleagues also evaluated the revised diagnostic criteria in a group of 49 patients and determined that the revised diagnostic criteria would not adequately capture patients in the early stage of the disease (40). However, the study did not include patients with ‘probable VKH,’ which leads to the question of whether this conclusion would still hold had this category been included. Overall, the revised diagnostic criteria are well-validated for VKH and appear to be the most frequently used in the clinical and research setting.

In 2018, Yang and colleagues published a new set of diagnostic criteria by retrospectively analyzing data from more than 1,100 patients with VKH and 1,100 patients with non-VKH associated uveitis (8). Patients are categorized into early or late phase of the disease as well as variant 1, 2, or 3 depending on the type of ocular manifestations. The criteria also incorporate findings of choroidal thickening from the EDI-OCT, achieving a higher sensitivity and NPV than the revised diagnostic criteria from 2001. However, critiques pointed out that PPV and NPV are actually lower in real populations since the prevalence is artificially set at 50% in the study (41). One of the criteria, “no evidence of infectious uveitis or accompanying systemic rheumatic diseases or evidence suggestive of other ocular disease entities,” was also criticized as it is broad catch-all statement that would leave VKH as the default diagnosis, not to mention require extensive workup.

In 2021, a classification criteria for VKH was developed by The SUN Working Group by applying machine learning on 1,012 cases of panuveitis, including 156 cases of early-stage VKH and 103 cases of late-stage VKH (9). The classification criteria, different from diagnostic criteria, optimized for specificity instead of sensitivity because the purpose of the diagnosis is for research. Therefore, clinicians should not use these criteria to diagnose patients with VKH and only use the data as reference.

Finally in 2022, Herbort and colleagues proposed a simplified diagnostic criteria for acute initial-onset VKH, in which bilateral disease and diffuse choroiditis on EDI-OCT or ICGA are requirements for the diagnosis of VKH (12). Authors emphasized the usefulness of ICGA in the early detection of VKH in the choroid, particularly in subclinical disease with choroidal involvement that is not evident on clinical exam or FA, and recommended EDI-OCT in settings without access to ICGA. No alternative options were provided to verify the presence of bilateral vitritis in the absence of ICGA or EDI-OCT. Other required criteria include the absence of ocular trauma or surgery before disease, bilateral involvement, exclusion of other infectious, inflammatory or masquerading entities, as well as criteria to exclude chronic VKH. In addition, exudative RD is listed as a “very helpful criterion” and disc hyperfluorescence and neurological or auditory findings as “helpful criterion”. However, there are no specifications on how these “helpful criteria” actually contribute to the diagnosis of VKH, especially in patients who don’t meet all the required criteria.

There is growing evidence that systemic corticosteroids may not be sufficient to prevent subclinical inflammation and development of chronic disease, even in a patient who had early initiation of corticosteroids. According to a systematic review including 16 studies and 802 patients with initial acute onset VKH, 44% had recurrent disease after treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (64). Sakata and colleagues reported a staggering 79% recurrence rate in Brazilian patients with VKH who were treated with high-dose corticosteroids within 1 month of disease onset (65). Other studies reported a smaller but a significant rate of recurrence despite early treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (62,66). Although some of the recurrence may have been prevented with an earlier initiation of corticosteroids, the high rate of recurrence suggests that there is a subset of patients with VKH that requires additional therapy with IMT.

Several studies support early initiation of IMT and even using it as a first-line treatment with corticosteroids. Yang and colleagues evaluated the effect of reduced corticosteroids in combination with one or more IMT, such as azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclosporine and cyclophosphamide, which showed that 98% of almost 1,000 patients with VKH achieved remission of uveitis (63). Urzua and colleagues reported that patients with poor glucocorticoid response had visual improvement associated with earlier initiation of IMT (67). Similarly, other studies reported better visual outcomes and remission in patients with chronic VKH when IMT was initiated early (28,68,69).

Azathioprine (Imuran, Promethus Labs, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) is an antimetabolite that is often used to treat chronic NIU. Kim and colleagues investigated the effect of azathioprine and systemic corticosteroids in a small number of patients with acute and chronic VKH, which revealed that while the addition of azathioprine resulted in corticosteroid-sparing effects, there was no significant difference in the cumulative corticosteroid dose, visual acuity, recurrence rate, or complications compared to patients who only received corticosteroids (70). Comparison of prednisone with azathioprine or cyclosporine showed that both regimen resulted in improved visual acuity and inflammation in patients with chronic VKH, but azathioprine had less glucocorticoid-sparing effect than cyclosporine (71).

Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Dava Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Newark, DE, and others) is another antimetabolite that is frequently used to treat chronic NIU. Kondo and colleagues reported three cases in which methotrexate was used in conjunction with systemic steroids to successfully control intraocular inflammation in patient with VKH, allowing two of the patients to stop systemic corticosteroids (72). It was also shown to control inflammation in seven out ten pediatric patients with acute VKH who were intolerant or unresponsive to initial treatment with systemic corticosteroids (73).

Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF; Cellcept, Genentech, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) is an antimetabolite used to treat chronic NIU and has been of primary interest to Abu El-Asrar and colleagues, who investigated the use of MMF as first-line treatment in patients with acute VKH. Their study showed that patients who received MMF in addition to systemic corticosteroids had better visual acuity as well as reduced rates of recurrence and complications compared to those who only received systemic corticosteroids (74). In patients with initial acute onset VKH, first-line treatment with MMF and systemic corticosteroids resulted in remission of disease in all patients with a visual acuity of 20/20 in 93.4% of eyes (75). Finally, a subanalysis of VKH patients from the First-line Antimetabolites as Steroid-sparing Treatment (FAST) trial on NIU showed that treatment with MMF or Methotrexate with systemic corticosteroids led to resolution of inflammation in a majority of patients (66%) with no statistical significant difference in efficacy between the two therapies (74% Methotrexate vs. 53% Mycophenolate Mofetil) (76).

Cyclosporine (Neoral Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., New York, NY, USA) is a calcineurin inhibitor that has been used to treat various NIU entities with varying efficacy (77). A study in Japan reported cyclosporine as the most common first choice IMT for patients with early and late stage VKH, but 5 out of 21 patients had recurrence and 14 patients had to discontinue due to side effects (78). A small case control study showed that a majority of patients with chronic VKH had remission of disease after a 3-month treatment with low-dose cyclosporine (79). Cyclosporine with prednisone improved visual acuity and aqueous flare in patients with chronic VKH and also had greater glucocorticoid-sparing effect compared to azathioprine and prednisone in a very small randomized controlled trial (N=21) (71).

Adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie, Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA) is a human monoclonal antibody that is directed against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and is the first-line therapy for Beh?et disease and second-line for juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (80). It is the only FDA-approved IMT for the treatment of non-infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis (81). Adalimumab was used to treat chronic recurrent VKH in several studies with mixed results. The largest study included 70 patients with chronic VKH who had failed therapy with IMT such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate in conjunction with high-dose corticosteroids. Patients in the study received over 6 months of adalimumab therapy and had improvement of subfoveal choroidal thickness and ICGA scores, leading to reduction of corticosteroids and cyclosporine doses. There were no significant improvements in visual acuity or flare counts, but a subset of patients with sunset glow fundus were found to have significant improvement in visual acuity after adalimumab treatment (82). Yang and colleagues evaluated the clinical outcomes of nine patients with chronic VKH who received an average of 10 months of adalimumab treatment, which showed improvement in BCVA, AC cell and vitritis but patients were not completely relapse free (83). In a study by Hiyama and colleagues, 11 out of 14 patients who received adalimumab as the only IMT had recurrence of inflammation and required the addition of methotrexate. While methotrexate as the only IMT also had high recurrence rates, the combination of adalimumab and methotrexate controlled the inflammation and eight out of 11 patients achieved remission of disease (78). A few case reports have showed clinical improvement and remission of disease in patients who received adalimumab therapy, two of which were on pediatric patients (84-86).

Infliximab (Remicade, Janssen Biotechn, Inc., Titusville, NJ, USA) is a chimeric monoclonal antibody against TNF-α with limited studies on treatment for VKH. There have only been case reports on the use of infliximab to treat VKH, which generally reported good visual outcomes and remission of disease (87-91). Methotrexate was often used in conjunction to prevent the formation of anti-infliximab antibodies (88-91). Of the three cases reported on the use of infliximab in pediatric patients, a 12 year-old Hispanic girl had persistent SRD and submacular fluid on infliximab that improved on cyclophosphamide treatment (91,92).

Rituximab (Rituxan, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA) is a monoclonal antibody to CD20 on B cells that has been studied in a small number of patients with VKH. In one study, nine patients with chronic recurrent VKH achieved remission after treatment with three infusions of Rituximab (92). Improvement in vision and choroidal thickness on EDI-OCT was also observed in five patients with poorly controlled VKH after infusions with rituximab (93). A ten-year-old girl had improved vision and remission of disease and another young patient had recovery of high-frequency hearing loss after treatment with rituximab (94,95).

While there are several renditions of the diagnostic criteria for VKH, the revised diagnostic criteria are the most well-validated. Rare ocular inflammatory conditions including SO, PS, and CSC should be considered in the differential diagnosis of VKH in addition to infectious and noninfectious causes of uveitis. For the treatment of VKH, studies showed that the early initiation of high-dose systemic corticosteroids was associated with better visual acuity outcomes and decrease rates of recurrence, but a subset of patients still developed recurrence or chronic disease. Studies on IMT show promising results and a combination therapy with corticosteroids has the potential to treat patients with VKH that did not respond to monotherapy with corticosteroids.

Peer Review File: Available at https://aes.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aes-23-3/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://aes.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/aes-23-3/coif). The series “The Retina and Systemic Disease” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. JGS has received small honoraria for a talk in March Berkley Optometry and CME writing activity Retina Specialist. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.