1、Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age- related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106ee116.Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age- related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106ee116.

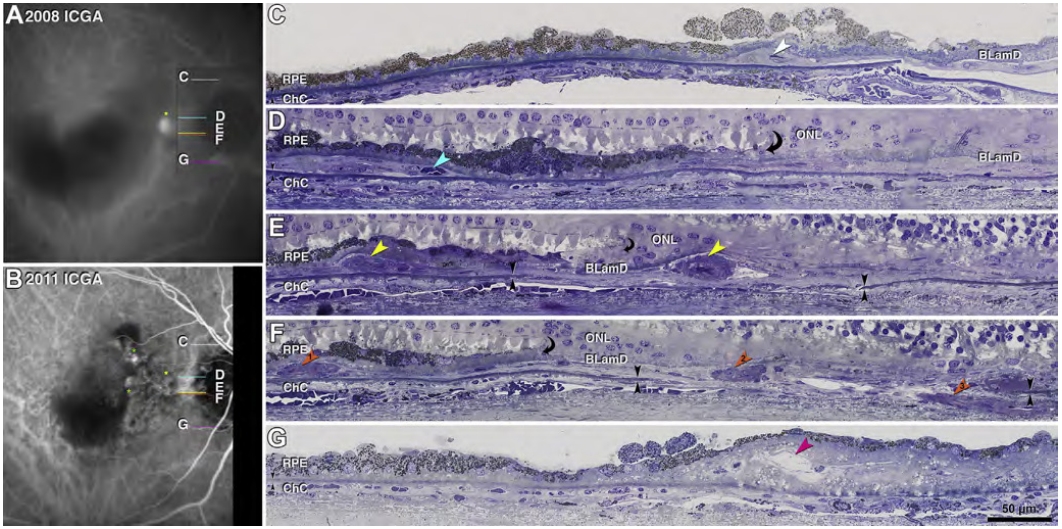

2、Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Messinger JD, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of aneurysmal type 1 neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration[J]. Ophthalmol Retina, 2019, 3(2): 99-111. DOI:10.1016/j.oret.2018.08.008. Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Messinger JD, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of aneurysmal type 1 neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration[J]. Ophthalmol Retina, 2019, 3(2): 99-111. DOI:10.1016/j.oret.2018.08.008.

3、Cheung CMG. Macular neovascularization and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: phenotypic variations, pathogenic mechanisms and implications in management[J]. Eye, 2024, 38(4): 659-667. DOI:10.1038/s41433-023-02764-w. Cheung CMG. Macular neovascularization and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: phenotypic variations, pathogenic mechanisms and implications in management[J]. Eye, 2024, 38(4): 659-667. DOI:10.1038/s41433-023-02764-w.

4、Ruamviboonsuk P, Lai TYY, Chen SJ, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: updates on risk factors, diagnosis, and treatments[J]. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol, 2023, 12(2): 184-195. DOI:10.1097/APO.0000000000000573. Ruamviboonsuk P, Lai TYY, Chen SJ, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: updates on risk factors, diagnosis, and treatments[J]. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol, 2023, 12(2): 184-195. DOI:10.1097/APO.0000000000000573.

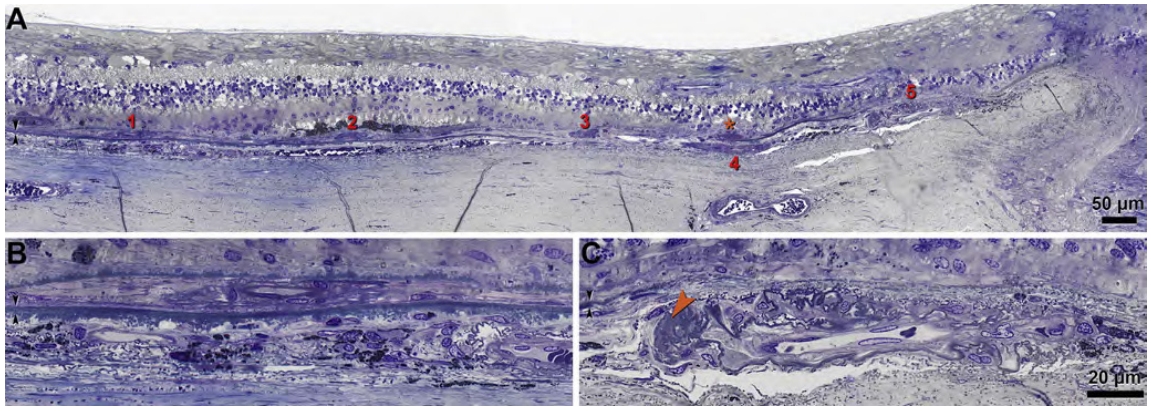

5、Liu G, Han L, Lu Y, et al. Clinicopathological study of the polypoidal lesions of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2022, 260(7): 2369-2377. DOI:10.1007/s00417-021-05525-1. Liu G, Han L, Lu Y, et al. Clinicopathological study of the polypoidal lesions of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2022, 260(7): 2369-2377. DOI:10.1007/s00417-021-05525-1.

6、Green WR, Enger C. Age-related macular degeneration histopathologic studies. The 1992 Lorenz E. Zimmerman Lecture[J]. Ophthalmology, 1993, 100(10): 1519-1535. DOI:10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31466-1. Green WR, Enger C. Age-related macular degeneration histopathologic studies. The 1992 Lorenz E. Zimmerman Lecture[J]. Ophthalmology, 1993, 100(10): 1519-1535. DOI:10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31466-1.

7、Curcio CA, Kar D, Owsley C, et al. Age-related macular degeneration, a mathematically tractable disease[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2024, 65(3): 4. DOI:10.1167/iovs.65.3.4. Curcio CA, Kar D, Owsley C, et al. Age-related macular degeneration, a mathematically tractable disease[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2024, 65(3): 4. DOI:10.1167/iovs.65.3.4.

8、Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Huisingh C, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration[J]. Retina, 2019, 39(4): 802-816. DOI:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002461. Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Huisingh C, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration[J]. Retina, 2019, 39(4): 802-816. DOI:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002461.

9、Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Messinger JD, et al. Neurodegeneration, gliosis, and resolution of haemorrhage in neovascular age-related macular degeneration, a clinicopathologic correlation[J]. Eye, 2021, 35(2): 548-558. DOI:10.1038/s41433-020-0896-y. Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Messinger JD, et al. Neurodegeneration, gliosis, and resolution of haemorrhage in neovascular age-related macular degeneration, a clinicopathologic correlation[J]. Eye, 2021, 35(2): 548-558. DOI:10.1038/s41433-020-0896-y.

10、Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Messinger JD, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor-treated type 3 neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration[J]. Ophthalmology, 2018, 125(2): 276-287. DOI:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.019. Li M, Dolz-Marco R, Messinger JD, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor-treated type 3 neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration[J]. Ophthalmology, 2018, 125(2): 276-287. DOI:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.019.

11、Li M, Huisingh C, Messinger J, et al. Histology of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: a multilayer approach[J]. Retina, 2018, 38(10): 1937-1953. DOI:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002182. Li M, Huisingh C, Messinger J, et al. Histology of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: a multilayer approach[J]. Retina, 2018, 38(10): 1937-1953. DOI:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002182.

12、Rosa RH Jr, Davis JL, Eifrig CWG. Clinicopathologic reports, case reports, and small case series: clinicopathologic correlation of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 2002, 120(4): 502-508. DOI:10.1001/archopht.120.4.502. Rosa RH Jr, Davis JL, Eifrig CWG. Clinicopathologic reports, case reports, and small case series: clinicopathologic correlation of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 2002, 120(4): 502-508. DOI:10.1001/archopht.120.4.502.

13、Nakashizuka H, Mitsumata M, Okisaka S, et al. Clinicopathologic findings in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2008, 49(11): 4729-4737. DOI:10.1167/iovs.08-2134. Nakashizuka H, Mitsumata M, Okisaka S, et al. Clinicopathologic findings in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2008, 49(11): 4729-4737. DOI:10.1167/iovs.08-2134.

14、Terasaki H, Miyake Y, Suzuki T, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy treated with macular translocation: clinical pathological correlation[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2002, 86(3): 321-327. DOI:10.1136/bjo.86.3.321. Terasaki H, Miyake Y, Suzuki T, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy treated with macular translocation: clinical pathological correlation[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2002, 86(3): 321-327. DOI:10.1136/bjo.86.3.321.

15、Kuroiwa S, Tateiwa H, Hisatomi T, et al. Pathological features of surgically excised polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy membranes[J]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2004, 32(3): 297-302. DOI:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00827.x. Kuroiwa S, Tateiwa H, Hisatomi T, et al. Pathological features of surgically excised polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy membranes[J]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2004, 32(3): 297-302. DOI:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00827.x.

16、Okubo A, Sameshima M, Uemura A, et al. Clinicopathological correlation of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy revealed by ultrastructural study[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2002, 86(10): 1093-1098. DOI:10.1136/bjo.86.10.1093. Okubo A, Sameshima M, Uemura A, et al. Clinicopathological correlation of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy revealed by ultrastructural study[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2002, 86(10): 1093-1098. DOI:10.1136/bjo.86.10.1093.

17、Lafaut BA, Aisenbrey S, Van den Broecke C, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy pattern in age-related macular degeneration: a clinicopathologic correlation[J]. Retina, 2000, 20(6): 650-654. DOI:10.1097/00006982-200011000-00010. Lafaut BA, Aisenbrey S, Van den Broecke C, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy pattern in age-related macular degeneration: a clinicopathologic correlation[J]. Retina, 2000, 20(6): 650-654. DOI:10.1097/00006982-200011000-00010.

18、Kishi S, Matsumoto H. A new insight into pachychoroid diseases: Remodeling of choroidal vasculature[J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2022, 260(11): 3405-3417. DOI:10.1007/s00417-022-05687-6. Kishi S, Matsumoto H. A new insight into pachychoroid diseases: Remodeling of choroidal vasculature[J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2022, 260(11): 3405-3417. DOI:10.1007/s00417-022-05687-6.

19、Reynders S, Lafaut BA, Aisenbrey S, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation in hemorrhagic age-related macular degeneration[J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2002, 240(4): 279-285. DOI:10.1007/s00417-002-0448-0. Reynders S, Lafaut BA, Aisenbrey S, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation in hemorrhagic age-related macular degeneration[J]. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2002, 240(4): 279-285. DOI:10.1007/s00417-002-0448-0.

20、Chen L, Messinger JD, Kar D, et al. Biometrics, impact, and significance of basal linear deposit and subretinal drusenoid deposit in age-related macular degeneration[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2021, 62(1): 33. DOI:10.1167/iovs.62.1.33.Chen L, Messinger JD, Kar D, et al. Biometrics, impact, and significance of basal linear deposit and subretinal drusenoid deposit in age-related macular degeneration[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2021, 62(1): 33. DOI:10.1167/iovs.62.1.33.

21、Chen L, Messinger JD, Sloan KR, et al. Abundance and multimodal visibility of soft drusen in early age-related macular degeneration: a clinicopathologic correlation[J]. Retina, 2020, 40(8): 1644-1648. DOI:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002893. Chen L, Messinger JD, Sloan KR, et al. Abundance and multimodal visibility of soft drusen in early age-related macular degeneration: a clinicopathologic correlation[J]. Retina, 2020, 40(8): 1644-1648. DOI:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002893.

22、Chen L, Yang P, Curcio CA. Visualizing lipid behind the retina in aging and age-related macular degeneration, via indocyanine green angiography (ASHS-LIA)[J]. Eye, 2022, 36(9): 1735-1746. DOI:10.1038/s41433-022-02016-3. Chen L, Yang P, Curcio CA. Visualizing lipid behind the retina in aging and age-related macular degeneration, via indocyanine green angiography (ASHS-LIA)[J]. Eye, 2022, 36(9): 1735-1746. DOI:10.1038/s41433-022-02016-3.

23、Curcio CA. Antecedents of soft drusen, the specific deposits of age-related macular degeneration, in the biology of human macula[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2018, 59(4): AMD182-AMD194. DOI:10.1167/iovs.18-24883. Curcio CA. Antecedents of soft drusen, the specific deposits of age-related macular degeneration, in the biology of human macula[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2018, 59(4): AMD182-AMD194. DOI:10.1167/iovs.18-24883.

24、Curcio CA. Soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration: biology and targeting via the oil spill strategies[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2018, 59(4): AMD160-AMD181. DOI:10.1167/iovs.18-24882. Curcio CA. Soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration: biology and targeting via the oil spill strategies[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2018, 59(4): AMD160-AMD181. DOI:10.1167/iovs.18-24882.

25、Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, et al. Aging, age-related macular degeneration, and the response-to-retention of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins[J]. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2009, 28(6): 393-422. DOI:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.001.Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, et al. Aging, age-related macular degeneration, and the response-to-retention of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins[J]. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2009, 28(6): 393-422. DOI:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.001.

26、Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, et al. Apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins in retinal aging and age-related macular degeneration[J]. J Lipid Res, 2010, 51(3): 451-467. DOI:10.1194/jlr.R002238. Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, et al. Apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins in retinal aging and age-related macular degeneration[J]. J Lipid Res, 2010, 51(3): 451-467. DOI:10.1194/jlr.R002238.

27、Curcio CA, Johnson M, Rudolf M, et al. The oil spill in ageing Bruch membrane[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2011, 95(12): 1638-1645. DOI:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300344. Curcio CA, Johnson M, Rudolf M, et al. The oil spill in ageing Bruch membrane[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2011, 95(12): 1638-1645. DOI:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300344.

28、Curcio CA, Millican CL. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age-related maculopathy[J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 1999, 117(3): 329-339. DOI:10.1001/archopht.117.3.329. Curcio CA, Millican CL. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age-related maculopathy[J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 1999, 117(3): 329-339. DOI:10.1001/archopht.117.3.329.

29、Nakajima M, Yuzawa M, Shimada H, et al. Correlation between indocyanine green angiographic findings and histopathology of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Jpn J Ophthalmol, 2004, 48(3): 249-255. DOI:10.1007/s10384-003-0057-4. Nakajima M, Yuzawa M, Shimada H, et al. Correlation between indocyanine green angiographic findings and histopathology of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy[J]. Jpn J Ophthalmol, 2004, 48(3): 249-255. DOI:10.1007/s10384-003-0057-4.

30、Zhang Y, Gan Y, Zeng Y, et al. Incidence and multimodal imaging characteristics of macular neovascularisation subtypes in Chinese neovascular age-related macular degeneration patients[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2024, 108(3): 391-397. DOI:10.1136/bjo-2022-322392.

Zhang Y, Gan Y, Zeng Y, et al. Incidence and multimodal imaging characteristics of macular neovascularisation subtypes in Chinese neovascular age-related macular degeneration patients[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2024, 108(3): 391-397. DOI:10.1136/bjo-2022-322392.