1、Willvonseder R, Goldstein NP, McCall JT, et al. A hereditary disorder

with dementia, spastic dysarthria, vertical eye movement paresis, gait

disturbance, splenomegaly, and abnormal copper metabolism[ J].

Neurology, 1973, 23(10): 1039-1049.Willvonseder R, Goldstein NP, McCall JT, et al. A hereditary disorder

with dementia, spastic dysarthria, vertical eye movement paresis, gait

disturbance, splenomegaly, and abnormal copper metabolism[ J].

Neurology, 1973, 23(10): 1039-1049.

2、Dix MR. Clinical observations upon the vestibular responses in certain

disorders of the central nervous system[ J]. Adv Otorhinolaryngol,

1970, 17: 118-128.Dix MR. Clinical observations upon the vestibular responses in certain

disorders of the central nervous system[ J]. Adv Otorhinolaryngol,

1970, 17: 118-128.

3、贾建平, 陈生第. 神经病学[M]. 第8版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2013.

JIA JP, CHEN SD. Neurology[M]. 8th ed. Beijing: People’s

Medical Publishing House, 2013.贾建平, 陈生第. 神经病学[M]. 第8版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2013.

JIA JP, CHEN SD. Neurology[M]. 8th ed. Beijing: People’s

Medical Publishing House, 2013.

4、Bayne T, Brainard D, Byrne RW, et al. What is cognition[ J]. Curr Biol,

2019, 29(13): R608-R615.Bayne T, Brainard D, Byrne RW, et al. What is cognition[ J]. Curr Biol,

2019, 29(13): R608-R615.

5、Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity[ J]. J

Intern Med, 2004, 256(3): 183-194.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity[ J]. J

Intern Med, 2004, 256(3): 183-194.

6、Hill NT, Mowszowski L, Naismith SL, et al. Computerized cognitive

training in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a

systematic review and meta-analysis[ J]. Am J Psychiatry, 2017, 174(4):

329-340.Hill NT, Mowszowski L, Naismith SL, et al. Computerized cognitive

training in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a

systematic review and meta-analysis[ J]. Am J Psychiatry, 2017, 174(4):

329-340.

7、Martin M, Clare L, Altgassen AM, et al. Cognition‐based interventions

for healthy older people and people with mild cognitive impairment[ J].

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011(1): CD006220.Martin M, Clare L, Altgassen AM, et al. Cognition‐based interventions

for healthy older people and people with mild cognitive impairment[ J].

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011(1): CD006220.

8、Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of

dementia: review[ J]. JAMA, 2019, 322(16): 1589-1599.Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of

dementia: review[ J]. JAMA, 2019, 322(16): 1589-1599.

9、Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Eur J Neurol

2018, 25(1): 59-70.Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Eur J Neurol

2018, 25(1): 59-70.

10、Prince MJ. World Alzheimer Report 2015: the global impact of

dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends:

Alzheimer’s Disease International[R]. London: Alzheimer’s Disease

International, 2015.Prince MJ. World Alzheimer Report 2015: the global impact of

dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends:

Alzheimer’s Disease International[R]. London: Alzheimer’s Disease

International, 2015.

11、Xu J, Wang J, Wimo A, et al. The economic burden of dementia in

China, 1990–2030: implications for health policy[ J]. Bull World

Health Organ, 2017, 95(1): 18.Xu J, Wang J, Wimo A, et al. The economic burden of dementia in

China, 1990–2030: implications for health policy[ J]. Bull World

Health Organ, 2017, 95(1): 18.

12、Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention,

intervention, and care[ J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(10113): 2673-2734.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention,

intervention, and care[ J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(10113): 2673-2734.

13、Petersen RC, Morris JC. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity

and treatment target[ J]. Arch Neurol, 2005, 62(7): 1160-1163.Petersen RC, Morris JC. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity

and treatment target[ J]. Arch Neurol, 2005, 62(7): 1160-1163.

14、Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--

beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International

Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment[ J]. J Intern Med, 2004,

256(3): 240-246.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--

beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International

Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment[ J]. J Intern Med, 2004,

256(3): 240-246.

15、Harper L, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, et al. An algorithmic approach to

structural imaging in dementia[ J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry,

2014, 85(6): 692-698.Harper L, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, et al. An algorithmic approach to

structural imaging in dementia[ J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry,

2014, 85(6): 692-698.

16、Duara R, Loewenstein DA, Potter E, et al. Medial temporal lobe atrophy

on MRI scans and the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease[ J]. Neurology,

2008, 71(24): 1986-1992.Duara R, Loewenstein DA, Potter E, et al. Medial temporal lobe atrophy

on MRI scans and the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease[ J]. Neurology,

2008, 71(24): 1986-1992.

17、Burton EJ, Barber R, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, et al. Medial temporal

lobe atrophy on MRI differentiates Alzheimer’s disease from dementia

with Lewy bodies and vascular cognitive impairment: a prospective

study with pathological verification of diagnosis[ J]. Brain, 2009,

132(Pt 1): 195-203.Burton EJ, Barber R, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, et al. Medial temporal

lobe atrophy on MRI differentiates Alzheimer’s disease from dementia

with Lewy bodies and vascular cognitive impairment: a prospective

study with pathological verification of diagnosis[ J]. Brain, 2009,

132(Pt 1): 195-203.

18、Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. Practice parameter:

diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the

Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of

Neurology[ J]. Neurology, 2001, 56(9): 1143-1153.Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. Practice parameter:

diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the

Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of

Neurology[ J]. Neurology, 2001, 56(9): 1143-1153.

19、Anderson TJ, MacAskill MR . Eye movements in patients with

neurodegenerative disorders[ J]. Nat Rev Neurol, 2013, 9(2): 74-85.Anderson TJ, MacAskill MR . Eye movements in patients with

neurodegenerative disorders[ J]. Nat Rev Neurol, 2013, 9(2): 74-85.

20、Bridgeman B. Conscious vs unconscious processes: the case of

vision[ J]. Theory Psychol, 1992, 2(1): 73-88.Bridgeman B. Conscious vs unconscious processes: the case of

vision[ J]. Theory Psychol, 1992, 2(1): 73-88.

21、Deubel H, Schneider WX. Delayed saccades, but not delayed manual

aiming movements, require visual attention shifts[ J]. Ann N Y Acad

Sci, 2003, 1004(1): 289-296.Deubel H, Schneider WX. Delayed saccades, but not delayed manual

aiming movements, require visual attention shifts[ J]. Ann N Y Acad

Sci, 2003, 1004(1): 289-296.

22、Girard B, Berthoz A. From brainstem to cortex: computational

models of saccade generation circuitry[ J]. Prog Neurobiol, 2005,

77(4): 215-251.Girard B, Berthoz A. From brainstem to cortex: computational

models of saccade generation circuitry[ J]. Prog Neurobiol, 2005,

77(4): 215-251.

23、Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Rivaud S, Gaymard B, et al. Cortical control of

saccades[ J]. Ann Neurol, 1995, 37(5): 557-567.Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Rivaud S, Gaymard B, et al. Cortical control of

saccades[ J]. Ann Neurol, 1995, 37(5): 557-567.

24、Coiner B, Pan H, Bennett ML, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of the

human eye movement network: a review and atlas[ J]. Brain Struct

Funct, 2019, 224(8): 2603-2617.Coiner B, Pan H, Bennett ML, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of the

human eye movement network: a review and atlas[ J]. Brain Struct

Funct, 2019, 224(8): 2603-2617.

25、Stuphorn V, Taylor TL, Schall JD. Performance monitoring by the

supplementary eye field[ J]. Nature, 2000, 408(6814): 857-860.Stuphorn V, Taylor TL, Schall JD. Performance monitoring by the

supplementary eye field[ J]. Nature, 2000, 408(6814): 857-860.

26、Parton A , Nachev P, Hodgson TL, et al. Role of the human

supplementary eye field in the control of saccadic eye movements[ J].

Neuropsychologia, 2007, 45(5): 997-1008.Parton A , Nachev P, Hodgson TL, et al. Role of the human

supplementary eye field in the control of saccadic eye movements[ J].

Neuropsychologia, 2007, 45(5): 997-1008.

27、Quaia C, Lefèvre P, Optican LM. Model of the control of saccades by

superior colliculus and cerebellum[ J]. J Neurophysiol, 1999, 82(2):

999-1018.Quaia C, Lefèvre P, Optican LM. Model of the control of saccades by

superior colliculus and cerebellum[ J]. J Neurophysiol, 1999, 82(2):

999-1018.

28、Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Müri RM, Nyffeler T, et al. The role of the human

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in ocular motor behavior[ J]. Ann N Y

Acad Sci, 2005, 1039: 239-251.Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Müri RM, Nyffeler T, et al. The role of the human

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in ocular motor behavior[ J]. Ann N Y

Acad Sci, 2005, 1039: 239-251.

29、Tulunay-Keesey U. Fading of stabilized retinal images[ J]. J Opt Soc

Am, 1982, 72(4): 440-447.Tulunay-Keesey U. Fading of stabilized retinal images[ J]. J Opt Soc

Am, 1982, 72(4): 440-447.

30、Kapoula Z, Yang Q, Otero-Millan J, et al. Distinctive features

of microsaccades in Alzheimer’s disease and in mild cognitive

impairment[ J]. Age, 2014, 36(2): 535-543.Kapoula Z, Yang Q, Otero-Millan J, et al. Distinctive features

of microsaccades in Alzheimer’s disease and in mild cognitive

impairment[ J]. Age, 2014, 36(2): 535-543.

31、Abadi RV, Gowen E. Characteristics of saccadic intrusions[ J]. Vision

Res 2004, 44(23): 2675-2690.Abadi RV, Gowen E. Characteristics of saccadic intrusions[ J]. Vision

Res 2004, 44(23): 2675-2690.

32、Martinez-Conde S. Fixational eye movements in normal and

pathological vision[ J]. Prog Brain Res, 2006, 154: 151-176.Martinez-Conde S. Fixational eye movements in normal and

pathological vision[ J]. Prog Brain Res, 2006, 154: 151-176.

33、Otero-Millan J, Macknik SL, Serra A, et al. Triggering mechanisms in

microsaccade and saccade generation: a novel proposal[ J]. Ann N Y

Acad Sci, 2011, 1233: 107-116.Otero-Millan J, Macknik SL, Serra A, et al. Triggering mechanisms in

microsaccade and saccade generation: a novel proposal[ J]. Ann N Y

Acad Sci, 2011, 1233: 107-116.

34、Martinez-Conde S, Otero-Millan J, Macknik SL. The impact of

microsaccades on vision: towards a unified theory of saccadic

function[ J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2013, 14(2): 83-96.Martinez-Conde S, Otero-Millan J, Macknik SL. The impact of

microsaccades on vision: towards a unified theory of saccadic

function[ J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2013, 14(2): 83-96.

35、Thier P, Ilg UJ. The neural basis of smooth-pursuit eye movements[ J].

Curr Opin Neurobiol, 2005, 15(6): 645-652.Thier P, Ilg UJ. The neural basis of smooth-pursuit eye movements[ J].

Curr Opin Neurobiol, 2005, 15(6): 645-652.

36、Fukushima K. Frontal cortical control of smooth-pursuit[ J]. Curr Opin

Neurobiol, 2003, 13(6): 647-654.Fukushima K. Frontal cortical control of smooth-pursuit[ J]. Curr Opin

Neurobiol, 2003, 13(6): 647-654.

37、Petit L, Haxby JV. Functional anatomy of pursuit eye movements in

humans as revealed by fMRI[ J]. J Neurophysiol, 1999, 82(1): 463-471.Petit L, Haxby JV. Functional anatomy of pursuit eye movements in

humans as revealed by fMRI[ J]. J Neurophysiol, 1999, 82(1): 463-471.

38、Yan YJ, Cui DM, Lynch JC. Overlap of saccadic and pursuit eye

movement systems in the brain stem reticular formation[ J]. J

Neurophysiol, 2001, 86(6): 3056-3060.Yan YJ, Cui DM, Lynch JC. Overlap of saccadic and pursuit eye

movement systems in the brain stem reticular formation[ J]. J

Neurophysiol, 2001, 86(6): 3056-3060.

39、赵堪兴, 杨培增. 眼科学[M]. 第8版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社,

2013: 23-24.

ZHAO KX, YANG PZ. Ophthalmology[M]. 8th ed. Beijing:

People’s Medical Publishing House, 2013: 23-24.赵堪兴, 杨培增. 眼科学[M]. 第8版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社,

2013: 23-24.

ZHAO KX, YANG PZ. Ophthalmology[M]. 8th ed. Beijing:

People’s Medical Publishing House, 2013: 23-24.

40、Sanford AM. Mild cognitive impairment[ J]. Clin Geriatr Med, 2017,

33(3): 325-337.Sanford AM. Mild cognitive impairment[ J]. Clin Geriatr Med, 2017,

33(3): 325-337.

41、Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Lyketsos CG, et al. Conversion to

dementia from mild cognitive disorder: the Cache County Study[ J].

Neurology, 2006, 67(2): 229-234.Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Lyketsos CG, et al. Conversion to

dementia from mild cognitive disorder: the Cache County Study[ J].

Neurology, 2006, 67(2): 229-234.

42、Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment: current research and clinical

implications[ J]. Semin Neurol, 2007, 27(1): 22-31.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment: current research and clinical

implications[ J]. Semin Neurol, 2007, 27(1): 22-31.

43、Yang Q, Wang T, Su N, et al. Specific saccade deficits in patients with

Alzheimer’s disease at mild to moderate stage and in patients with

amnestic mild cognitive impairment[ J]. Age, 2013, 35(4): 1287-1298.Yang Q, Wang T, Su N, et al. Specific saccade deficits in patients with

Alzheimer’s disease at mild to moderate stage and in patients with

amnestic mild cognitive impairment[ J]. Age, 2013, 35(4): 1287-1298.

44、Chehrehnegar N, Nejati V, Shati M, et al. Behavioral and cognitive

markers of mild cognitive impairment: diagnostic value of saccadic eye

movements and Simon task[ J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2019, 31(11):

1591-1600.Chehrehnegar N, Nejati V, Shati M, et al. Behavioral and cognitive

markers of mild cognitive impairment: diagnostic value of saccadic eye

movements and Simon task[ J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2019, 31(11):

1591-1600.

45、Alichniewicz KK, Brunner F, Klünemann HH, et al. Neural correlates

of saccadic inhibition in healthy elderly and patients with amnestic mild

cognitive impairment[ J]. Front Psychol, 2013, 4: 467.Alichniewicz KK, Brunner F, Klünemann HH, et al. Neural correlates

of saccadic inhibition in healthy elderly and patients with amnestic mild

cognitive impairment[ J]. Front Psychol, 2013, 4: 467.

46、Fletcher WA, Sharpe JA. Saccadic eye movement dysfunction in

Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Ann Neurol, 1986, 20(4): 464-471.Fletcher WA, Sharpe JA. Saccadic eye movement dysfunction in

Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Ann Neurol, 1986, 20(4): 464-471.

47、Shafiq-Antonacci R, Maruff P, Masters C, et al. Spectrum of saccade

system function in Alzheimer disease[ J]. Arch Neurol, 2003, 60(9):

1272-1278.Shafiq-Antonacci R, Maruff P, Masters C, et al. Spectrum of saccade

system function in Alzheimer disease[ J]. Arch Neurol, 2003, 60(9):

1272-1278.

48、Kahana Levy N, Lavidor M, Vakil E. Prosaccade and antisaccade

paradigms in persons with Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analytic

review[ J]. Neuropsychol Rev, 2018, 28(1): 16-31.Kahana Levy N, Lavidor M, Vakil E. Prosaccade and antisaccade

paradigms in persons with Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analytic

review[ J]. Neuropsychol Rev, 2018, 28(1): 16-31.

49、Yang Q, Wang T, Su N, et al. Long latency and high variability in

accuracy-speed of prosaccades in Alzheimer’s disease at mild to

moderate stage[ J]. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra, 2011, 1(1):

318-329.Yang Q, Wang T, Su N, et al. Long latency and high variability in

accuracy-speed of prosaccades in Alzheimer’s disease at mild to

moderate stage[ J]. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra, 2011, 1(1):

318-329.

50、Peltsch A, Hemraj A, Garcia A, et al. Saccade deficits in amnestic mild

cognitive impairment resemble mild Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Eur J

Neurosci, 2014, 39(11): 2000-2013.Peltsch A, Hemraj A, Garcia A, et al. Saccade deficits in amnestic mild

cognitive impairment resemble mild Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Eur J

Neurosci, 2014, 39(11): 2000-2013.

51、Garbutt S, Matlin A, Hellmuth J, et al. Oculomotor function in

frontotemporal lobar degeneration, related disorders and Alzheimer’s

disease[ J]. Brain, 2008, 131(Pt 5): 1268-1281.Garbutt S, Matlin A, Hellmuth J, et al. Oculomotor function in

frontotemporal lobar degeneration, related disorders and Alzheimer’s

disease[ J]. Brain, 2008, 131(Pt 5): 1268-1281.

52、Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain[ J].

Annu Rev Neurosci, 1990, 13: 25-42.Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain[ J].

Annu Rev Neurosci, 1990, 13: 25-42.

53、Kaufman LD, Pratt J, Levine B, et al. Executive deficits detected in mild

Alzheimer’s disease using the antisaccade task[ J]. Brain Behav, 2012,

2(1): 15-21.Kaufman LD, Pratt J, Levine B, et al. Executive deficits detected in mild

Alzheimer’s disease using the antisaccade task[ J]. Brain Behav, 2012,

2(1): 15-21.

54、Crawford TJ, Higham S, Mayes J, et al. The role of working memory

and attentional disengagement on inhibitory control: effects of aging

and Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Age, 2013, 35(5): 1637-1650.Crawford TJ, Higham S, Mayes J, et al. The role of working memory

and attentional disengagement on inhibitory control: effects of aging

and Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Age, 2013, 35(5): 1637-1650.

55、Currie J, Ramsden B, McArthur C, et al. Validation of a clinical

antisaccadic eye movement test in the assessment of dementia[ J]. Arch

Neurol, 1991, 48(6): 644-648.Currie J, Ramsden B, McArthur C, et al. Validation of a clinical

antisaccadic eye movement test in the assessment of dementia[ J]. Arch

Neurol, 1991, 48(6): 644-648.

56、Abel LA, Unverzagt F, Yee RD. Effects of stimulus predictability and

interstimulus gap on saccades in Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Dement

Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2002, 13(4): 235-243.Abel LA, Unverzagt F, Yee RD. Effects of stimulus predictability and

interstimulus gap on saccades in Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Dement

Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2002, 13(4): 235-243.

57、Heuer HW, Mirsky JB, Kong EL, et al. Antisaccade task reflects cortical

involvement in mild cognitive impairment[ J]. Neurology, 2013,

81(14): 1235-1243.Heuer HW, Mirsky JB, Kong EL, et al. Antisaccade task reflects cortical

involvement in mild cognitive impairment[ J]. Neurology, 2013,

81(14): 1235-1243.

58、Bylsma FW, Rasmusson DX, Rebok GW, et al. Changes in visual

fixation and saccadic eye movements in Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Int J

Psychophysiol, 1995, 19(1): 33-40.Bylsma FW, Rasmusson DX, Rebok GW, et al. Changes in visual

fixation and saccadic eye movements in Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. Int J

Psychophysiol, 1995, 19(1): 33-40.

59、Boxer AL, Garbutt S, Rankin KP, et al. Medial versus lateral frontal lobe

contributions to voluntary saccade control as revealed by the study of

patients with frontal lobe degeneration[ J]. J Neurosci, 2006, 26(23):

6354-6363.Boxer AL, Garbutt S, Rankin KP, et al. Medial versus lateral frontal lobe

contributions to voluntary saccade control as revealed by the study of

patients with frontal lobe degeneration[ J]. J Neurosci, 2006, 26(23):

6354-6363.

60、Zaccara G, Gangemi PF, Muscas GC, et al. Smooth-pursuit eye

movements: alterations in Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. J Neurol Sci, 1992,

112(1-2): 81-89.Zaccara G, Gangemi PF, Muscas GC, et al. Smooth-pursuit eye

movements: alterations in Alzheimer’s disease[ J]. J Neurol Sci, 1992,

112(1-2): 81-89.

61、Pavisic IM, Firth NC, Parsons S, et al. Eyetracking metrics in young

onset Alzheimer’s disease: a window into cognitive visual functions[ J].

Front Neurol, 2017, 8: 377.Pavisic IM, Firth NC, Parsons S, et al. Eyetracking metrics in young

onset Alzheimer’s disease: a window into cognitive visual functions[ J].

Front Neurol, 2017, 8: 377.

62、Hutton JT, Nagel JA, Loewenson RB. Eye tracking dysfunction in

Alzheimer-type dementia[ J]. Neurology, 1984, 34(1): 99-102.Hutton JT, Nagel JA, Loewenson RB. Eye tracking dysfunction in

Alzheimer-type dementia[ J]. Neurology, 1984, 34(1): 99-102.

63、Moser A, K?mpf D, Olschinka J. Eye movement dysfunction in

dementia of the Alzheimer type[ J]. Dementia, 1995, 6(5): 264-268.Moser A, K?mpf D, Olschinka J. Eye movement dysfunction in

dementia of the Alzheimer type[ J]. Dementia, 1995, 6(5): 264-268.

64、Fotiou DF, Stergiou V, Tsiptsios D, et al. Cholinergic deficiency in

Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: evaluation with pupillometry[ J].

Int J Psychophysiol, 2009, 73(2): 143-149.Fotiou DF, Stergiou V, Tsiptsios D, et al. Cholinergic deficiency in

Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: evaluation with pupillometry[ J].

Int J Psychophysiol, 2009, 73(2): 143-149.

65、Fotiou F, Fountoulakis KN, Tsolaki M, et al. Changes in pupil reaction

to light in Alzheimer’s disease patients: a preliminary report[ J]. Int J

Psychophysiol, 2000, 37(1): 111-120.Fotiou F, Fountoulakis KN, Tsolaki M, et al. Changes in pupil reaction

to light in Alzheimer’s disease patients: a preliminary report[ J]. Int J

Psychophysiol, 2000, 37(1): 111-120.

66、Crawford TJ, Higham S, Renvoize T, et al. Inhibitory control of saccadic

eye movements and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease[ J].

Biol Psychiatry, 2005, 57(9): 1052-1060.Crawford TJ, Higham S, Renvoize T, et al. Inhibitory control of saccadic

eye movements and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease[ J].

Biol Psychiatry, 2005, 57(9): 1052-1060.

67、LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning[ J]. Nature, 2015,

521(7553): 436-444.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning[ J]. Nature, 2015,

521(7553): 436-444.

68、Poplin R, Varadarajan AV, Blumer K, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular

risk factors from retinal fundus photographs via deep learning[ J]. Nat

Biomed Eng, 2018, 2(3): 158-164.Poplin R, Varadarajan AV, Blumer K, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular

risk factors from retinal fundus photographs via deep learning[ J]. Nat

Biomed Eng, 2018, 2(3): 158-164.

69、Long E, Liu Z, Xiang Y, et al. Discrimination of the behavioural

dynamics of visually impaired infants via deep learning[ J]. Nat Biomed

Eng, 2019, 3(11): 860-869.Long E, Liu Z, Xiang Y, et al. Discrimination of the behavioural

dynamics of visually impaired infants via deep learning[ J]. Nat Biomed

Eng, 2019, 3(11): 860-869.

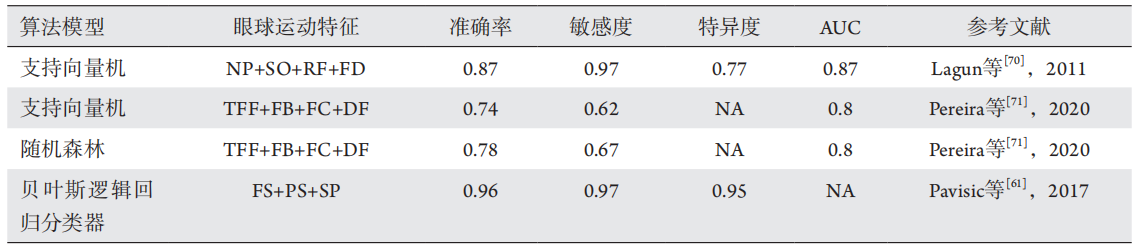

70、Lagun D, Manzanares C, Zola SM, et al. Detecting cognitive

impairment by eye movement analysis using automatic classification

algorithms[ J]. J Neurosci Methods, 2011, 201(1): 196-203.Lagun D, Manzanares C, Zola SM, et al. Detecting cognitive

impairment by eye movement analysis using automatic classification

algorithms[ J]. J Neurosci Methods, 2011, 201(1): 196-203.

71、Pereira ML, Camargo M, Bellan AFR, et al. Visual search efficiency in

mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: an eye movement

study[ J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2020, 75(1): 261-275.Pereira ML, Camargo M, Bellan AFR, et al. Visual search efficiency in

mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: an eye movement

study[ J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2020, 75(1): 261-275.