Abstract: The inverted retina is a basic characteristic of the vertebrate eye. This implies that vertebrates must have a common ancestor with an inverted retina. Of the two groups of chordates, cephalochordates have an inverted retina and urochordates a direct retina. Surprisingly, recent genetics studies favor urochordates as the closest ancestor to vertebrates. The evolution of increasingly complex organs such as the eye implies not only tissular but also structural modifications at the organ level. How these configurational modifications give rise to a functional eye at any step is still subject to debate and speculation. Here we propose an orderly sequence of phylogenetic events that closely follows the sequence of developmental eye formation in extant vertebrates. The progressive structural complexity has been clearly recorded during vertebrate development at the period of organogenesis. Matching the chain of increasing eye complexity in Mollusca that leads to the bicameral eye of the octopus and the developmental sequence in vertebrates, we delineate the parallel evolution of the two-chambered eye of vertebrates starting with an early ectodermal eye. This sequence allows for some interesting predictions regarding the eyes of not preserved intermediary species. The clue to understanding the inverted retina of vertebrates and the similarity between the sequence followed by Mollusca and chordates is the notion that the eye in both cases is an ectodermal structure, in contrast to an exclusively (de novo) neuroectodermal origin in the eye of vertebrates. This analysis places cephalochordates as the closest branch to vertebrates contrary to urochordates, claimed as a closer branch by some researchers that base their proposals in a genetic analysis.

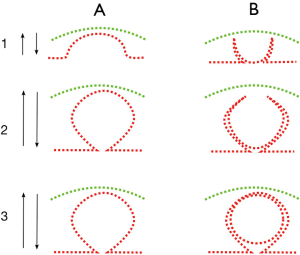

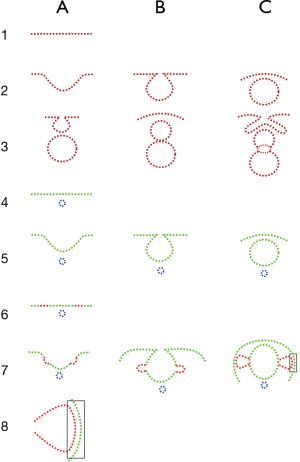

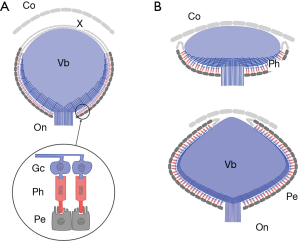

Ever since Darwin, the “eye problem” has consisted of explaining a progressive acquisition of complexity with incremental functional gain. This task has been satisfactorily accomplished with the eye of invertebrates, including the bicameral eye of the octopus (Figure 1A) (1), considered to be as complex as that of higher vertebrates. In relation to the vertebrate eye (Figure 1B), on the contrary, the sequence is not as clear, partially because of the reduced number of extant intermediary species, compared to invertebrates.

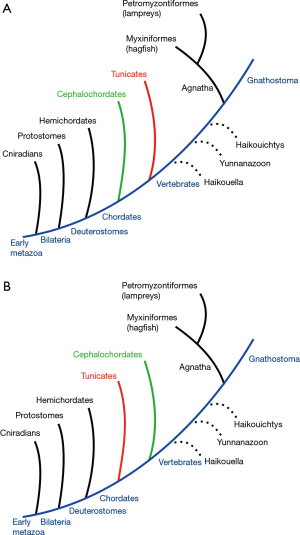

Regarding the relationship, and continuity, between the invertebrate and vertebrate eye, although the basic tenet that both share ectodermal origins had been established for decades, some doubts persist. When the phylogenetic trees of the chordates and first vertebrates are considered (Figure 2) (phylogenetic tree), the issue concerning eye morphology revolves around two possible orderings. There is a consensus that, among deuterostomes, echinoderms and hemichordates form a clade, and that urochordates, cephalochordates, and vertebrates form another clade (3). However, recent reviews (3,4) present mounting evidence that within the chordate clade, cephalochordates diverged first, and that urochordates and vertebrates are more closely related not only genetically but also possessing common structures that are not present in cephalochordates (5).

We can consider two polemics that should be confronted in the evolution of the eye. One of the open subjects is the relationship between vertebrates and early chordates, which are themselves invertebrates: are vertebrates more closely related to urochordates or to cephalochordates? Two; is the inverted retina a de novo and exclusive feature of vertebrates or is there a continuity with the invertebrate eye?

Firstly, chordates are frequently rearranged based on renewed genetic analyses. The crucial role played by the gene Pax6 in eye morphogenesis, very early in evolution, persists also in humans. However, although Branchiostoma lanceolatum appears to be the direct precursor of vertebrates based on morphological grounds (6), it has been displaced in favor of urochordates (subphyla Tunicata) based on genetic similarity (2,5,7). Secondly, the fossil record linking the first vertebrates is relatively poor, and extant species are reduced to disconnected links: the hagfish and lampreys, both included in the superclass agnatha (without jaws), on one side. On the other, the vertebrate superclass gnathostomata (jawed mouths), which includes the remaining vertebrate classes: chondrichthyes (sharks), osteichthyes (bony fishes), amphibia, reptilia, aves, and mammalia. At the basic structural level, the eye of the lamprey has already reached the summit of the bicameral eye, and consequently, the relationship between the lamprey and the rest of vertebrates is straightforward (Figure 2) (8).

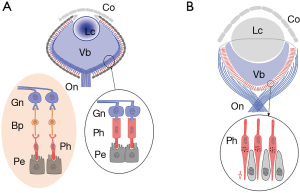

The problem, then, is how to link cephalochordates, urochordates, and Craniata, the only niches with surviving species. Among cephalochordates, Branchiostoma lanceolatum (amphioxus) and related species are tiny animals with rudimentary eyes (Figure 3A) (9). The next group, urochordates is still more chance-ridden, as the eyes are present just in some species and only in the larval stage, as happens with tunicates (Figure 3B,C) (10). Apart from the fossil record, to which we will return below, this is all that is left of the eye evolution in vertebrates. It is thus not surprising that opinions in this matter diverge.

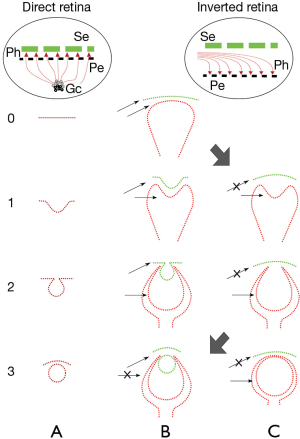

The intention of this communication is to present a hypothetical solution to the problematic relationship between the eyes in invertebrates and vertebrates posed as two alternatives: (I) the evolution of the eyes is homologous, or (II) the eye has originated independently, and converged, at least twice. We lean towards (I) and tentatively propose the missing links. We approach this task by outlining a sequence followed by vertebrates during development and collate those stages with the much better-known sequence leading to the bicameral eye among invertebrates (mainly Mollusca, to the exclusion of composite eyes). A view of this process (summarized in Figure 4) could provide some insight into the missing intermediary stages that purportedly disappeared over evolution, and may help to reorder the evolutionary tree along this sequence. This basic framework is presented in the hope that it will serve to relate the body of data on the tissular/cellular evolution of the eye that has accumulated over recent decades. In this context, a distinction should be made to the terminology. It is not enough to consider, in the evolution of the retina, the development of a single or double layer, but it is critical to assert if the double layer is the result of invagination versus cell-replication. For this reason, we insist in the invagination process all along and situate the first inverted retina in the cephalochordates, although it is not double layered, and point in the ascidian’s retina as direct. Other researchers have tried to situate the arising of a double or triple layered retina without referring to the invagination process (8).

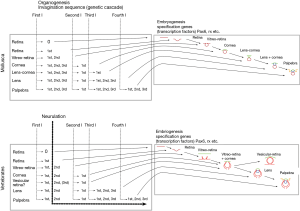

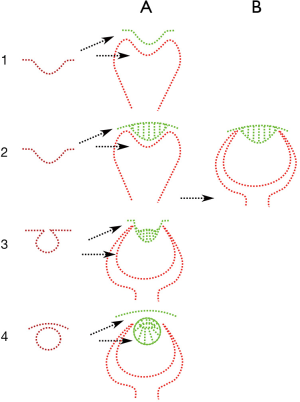

The organogenesis of the eye in vertebrates can be schematized as a process of invagination that repeats several times from the edge of the first (ectodermal) retinal cup, giving rise successively to structures such as the lens, cornea, and palpebrae (Figures 5,6). The formation of a series of vesicles that accumulate one after the other, suggests that the same chain of genetic events is repeated time and again in different phyla, as is the process involving the resetting of the same initial chain of events. Once formed, a complete or incomplete vesicle would follow its proper fate regarding the differentiation of cells to lens fibers, corneal epithelium, retinal cells, etc. Our argument would allocate more weight to the morphological continuity of this line of successive invaginations than to genetic proximity. The genetic disparity can be adequately explained by other processes. It has been argued that genome duplication in vertebrates has been followed by massive gene losses. Extant gene groups of a lineage can, then, vary substantially depending on which genes were preserved or lost (11).

Studies on neurogenesis of ascidians point to a similarity to all groups of chordates, including vertebrates (10,12). However, those studies fail to highlight a key difference separating them from vertebrates and cephalochordates as well. The difference is the position of the photoreceptor in the visual organ. It is a crucial fact that, as the dorsal tube is limited to the caudal region, the eyes originate in the anterior sensorial vesicle which is not part of the tubular neural system. The position of the retina is direct, instead of inverted as in amphioxus and all vertebrates. Urochordates have a dorsal neural tube roughly resembling that of vertebrates plus an anterior sensorial organ with the characteristics of mollusks and other invertebrates. Although the ocellus of Ciona intestinalis is difficult to interpret (Figure 3B), it can be compared with close species as the larva of Aplidium constellatum (Figure 3C), both displaying a direct retina. Here the eye and its structure are the key to the relationships. It is important to separate the orientation of the retina and the level of complexity. Structural complexity is even higher in late Mollusca with bicameral eyes and a direct retina, as in the octopus (13) (Figure 1).

An inverted retina is present in the unique eye of amphioxus, but not in the urochordates, and this feature, perhaps more than any other, characterizes the vertebrate eye. The clue to understanding the inverted retina of vertebrates and the continuity between the invertebrate (mollusca) and the vertebrate eye is the notion that in both cases the eye is an ectodermal structure, contrary to having a purely neuroectodermal origin in the eye of vertebrates. Here, we propose a lineage of successive eye modifications based on the eye of amphioxus because urochordates lack the critical feature of an inverted retina.

Our Interpretation organizes current aspects of the eye evolution in vertebrates and invertebrates under the underlying assumption that the cameral eye in both groups shares a common ectodermal origin (Figures 5,6). The basis of this assumption is the supported by the activity of Pax6 as a master control gene for eye morphogenesis shared both by vertebrates and invertebrates, together with the fact that this gene is activated in chordates, during development, before the neural tube begins to form. The straightforward explanation for the inverted retina of vertebrates is that the original ancestor already had an inverted retina, as happens to be the case of the amphioxus.

Horowitz (14) proposed a mechanism of retrograde evolution for the evolution of biochemical pathways in which the enzymes in the pathway are progressively added in a retrograde fashion so that the chain starts with simpler molecules each time a new step is added. Based on similar reasoning, Gehring and Ikeo [1999] (6) proposed that any morphogenetic (or developmental) pathways evolve by intercalary evolution. That is, starting from a prototype, selection optimizes it with the consecutive introduction of new genes into the cascade, a process that these researchers call intercalary evolution. In our subject, a reading of the organogenetic phase of eye development shows that in complex organisms, such as mollusks, a chain can be assembled using extant animals in which progressive complexity is progressively added to the eye in a step-by-step fashion (Figures 5,6). This provides the eye with gradual increments in functionality, providing the bearers a new feature and thus an adaptive edge. This progressive uninterrupted chain has been construed based mainly on mollusks with the occasional reference to other phylae or paraphylae. We contend it is feasible to extend the chain also to chordates and vertebrates. To do so, since vertebrate eyes share the basic structure of bicameral eyes, we take the human development of the eye as a guide. Divergence in tissular details is huge among vertebrates, but the organogenesis follows identical lines. The most basic vesicular architecture of eye morphogenesis could serve as a scaffold for subsequent refinement in gene expression and tissue structure. However, it is easy to understand that organogenetic changes have a major influence because they precede any later tissue differentiation. The use of development as a guide for evolution is a major tenet of the present-day evo-devo approach to evolution. This leaves behind the initial, understandably distorted, views of the early days in which those ideas were discussed by Haeckel and Sedgwick (15). A true and complete bicameral eye is composed, from back to front, of a vitreous chamber surrounded by the retina, ciliary body, and iris, and occupied by an histic vitreous body, a tissular or histic crystalline lens, an anterior chamber, a cornea and, finally, histic eyelids (palpebrae) fused or separated (Figure 1A,B).

When the complete sequence in the mature eye of invertebrates is compared to the organogenetic stages of development of vertebrates, most stages coincide with equivalent complexity. For some stages, the availability of extant specimens shows the pertinence of the model. For other stages, there are no living or fossil examples and therefore, any examples are mere predictions of the model. The basic outline that progressively gives rise to the most elemental structures of the eye suggests that the generative process is not exclusive to the eye. On the contrary, the mechanism that gives rise to the eye structures is a fundamental movement present since the earliest and most primal stages of development. This is found in the common process of invagination, as present in the initial stages of gastrulation, which gives rise to the optic cup (retina) and repeated to originate the lens and cornea-palpebrae. This local invagination is also similar in shape to the more extensive process of neurulation, or formation of the neural tube (Figure 5). As shown in Figure 4, neurulation as an invagination process involves a major area, including the already determined ocular placodes, and results in a tubular, rather than vesicular, shape.

A depiction of consecutive stages from the flat to the bicameral eye (Figures 5,6) shows how new structures are successively added to the previous structure in such a way that what is external in one species may be internal in a more evolved one. For instance, what is a cornea in one species is covered up after the onset of a new invagination and transforms into a lens. When a new structure (e.g., the lens) is starting to form, it is necessary for incomplete stages also to imply a functional gain in comparison to previous stages or at least to be equally functional. An example is the formation of a lenti-cornea prior to the separation of the lens as an independent vesicle. The size increase of the central cells of the corneal epithelium enhances the refractive ability of the cornea, which is successively increased in later stages. The size of the eye and the animal can be decisive in the appearance and preservation of new features, such as typically, the lens. We have cited examples of unicellular lenses (Figure 3A,B). In a very small animal, a transition from a cornea to a lens can start with the simple feature of the increased size of the central cells within the surface epithelium.

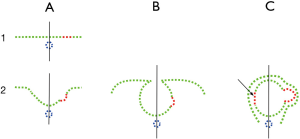

There is some imprecision in the nomenclature regarding those structures. Some descriptions show a lack of cornea and an external lens. Clearly, an integrated view of the generation process of the eye structures would clarify this subject. The name of the structure depends on the position in the eye. This reinforces our use of the term histological layer according to its position and functional role and not using a term based on mere resemblance, as, for instance, in the case of a squid, as lacking a cornea but having a lens as the first refractive surface. There are Mollusca that lack a cornea, including the stenopeic eye of the Nautilus, and the first refractive surface will always be a cornea, whether anhistic or epithelial, etc. Then the lenticular shape of the cornea would not contradict the nomenclature. As soon as the next vesicle appears in the phylogenetic sequence, the lenticular cornea gives rise to a true crystalline lens and the new surface structure is a cornea (Figure 7).

Following this criterion, the anterior surface of the cameral eye is the cornea. The first invaginations of the surface epithelium do not in themselves confer any apparent refractive advantage. However, if we follow the case of the squid with a cornea-lens (16), the invagination is preceded by, or coincidental with, an increase in the size of the epithelial cells conferring a dioptric capability superior to that of the flat cornea (Figure 7). The greater thickness of the central epithelial cells and tapering towards the edges is a clear refractive acquisition, and an advantage in focusing the light and in sensitivity to light in the first place. In bigger eyes, this secondarily also enhances the capability of image formation. In the case of the Mollusca, as the vitreoretinal vesicle contacts with the invaginated epithelia, a similar increment in cell size boosts the refractive capabilities of the cornea-lens. Then, what would be a crystalline lens has already afforded incipient refractive capability. It could be argued that once the genetic cascade that has produced the first, or vitreoretinal, vesicle has been successfully run, it could be repeated straightforwardly in all its phases at once, giving rise to a detached vesicular crystalline lens. This is also a possibility, but during development, the first signs of the invagination of the crystalline lens include the increase in epithelium thickness, so that the formation of a detached crystalline lens has probably been gradual, and this has in all likelihood happened also in vertebrates. The initial phase is then a globular cornea by a size increase if the epithelium and the differential multiplication of the borders give rise to a progressively encapsulated cornea and finally a detached vesicular crystalline lens (Figure 7).

In the case of eyelid formation, the process of invagination involves only the ring external to the ocular structure. It is ring shaped and peripheral to the cornea, while the central ocular structures are no longer modified. This progressive invagination process has many examples from different species, and even Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish) already may have incomplete eyelids. The same happens with the Osteichthyes in relation to the fatty lid and the nictitating membrane. This process is a variant of the same invagination movement. The similarity of both processes is evident in the fusion of the palpebrae in mammals, which separate shortly before birth, or never cleave but became transparent as in some Ophidia. In short, it seems that the same invagination process occurs with variations in one, two, three, or four successive stages along the branches of the evolutionary tree.

The evolution of the eye from invertebrates to vertebrates is a corollary to this theory. The critical point is the explanation of the inverted retina. According to the hypothesis, the retina is inverted because the species that gave birth to the neural tube already had eyes. That is, it had ectodermic eyes, which underwent a neurulation process that included the cephalic portion expressing the eyes. One exercise in order to find a solution in the continuity, or lack of it, between vertebrates and invertebrates, regarding the eye, would be to speculate upon the possibilities of vertebrates having eyes with direct retinas (Figure 8). Two possibilities would be:

Curiously enough, alternative actually exists in the urochordates. The eye of the ascidian tadpole (Figure 1B) is not affected in its development by the notochord and displays a direct retina (9,17). Regarding vertebrate genomes, evidence has mounted for large-scale genome duplications on the vertebrate stem, with a parallel loss of most gene duplicates (18-20). This fact substantially obscures the establishment of genetic similarities or differences. In spite of strong morphological arguments to prove the contrary, Delsuc’s claim, that urochordates are closer to vertebrates than is amphioxus, has antecedents (10). The morphological argument defended here opposes that view.

The second alternative

Some authors (23,24) have considered the eyes of hagfishes (Figure 9) (25) to be degenerate because of the absence of a lens, intra- and extraocular eye muscles, a clear transparent cornea, and other features not present in the common vertebrate eye. They pointed to ancestors with functional bicameral eyes, i.e., with all those elements that were later lost (26). It was Lamb and collaborators (4,27) who considered that they may represent a missing link in eye evolution, filling a void between the simple eyes of tunicates and the image-forming eyes of lampreys.

As mentioned above, one of the main problems in understanding the origin of the vertebrate eye is the lack of extant intermediary animals. One proof against the validity of the approach presented here would be to see whether it is useful in predicting the stages that vertebrates had to go through before reaching the present conformation. In the Consequences section, an attempt will be made to predict some of the missing links. Size is important because, in a small animal, an inverted retina is no less functional than a direct one. The morphological changes are feasible if they take place in very small animals. Among these, a size increase and preservation in the fossil record would be a matter of chance. That the hagfish is large compared to amphioxus suggests that its ancestors, all lacking a lens, were progressively enlarging. There could then be a fossil register of fishes with eyes formed only by a retina and cornea but without a lens. The retinal cup would progressively close its anterior segment, giving rise to a stenopeic eye and finally to a vesicular eye Sequence 1C→4C of Figure 5. A different line, 1B→4B of Figure 5, would produce an eye with a retina, lens, and cornea. This is the line with a bicameral eye in which lampreys and the rest of vertebrates would appear.

The growing size of the eye is one process while the deepening of the optic cup is a different process. As depicted in Figure 10, the deepening of the first cup has to be neutralized by an inverse cup of the same depth. According to the model, the same process that results in the first cup is triggered again to form the second, inverse, cup. These processes, in theory, will end in the complete closing of the retinal cup, giving rise to a separate (or detached) retinal vesicle, as happens in invertebrates with the vesicular eye of the snail (helix helix). The predictions would also cast some light on the possibility of some eyes being a degeneration of previous functional eyes, as claimed in the case of the hagfish, as discussed in the next section. The parallel sequences of eye evolution among invertebrates and vertebrates are summarized in Figure 4.