BACKGROUND

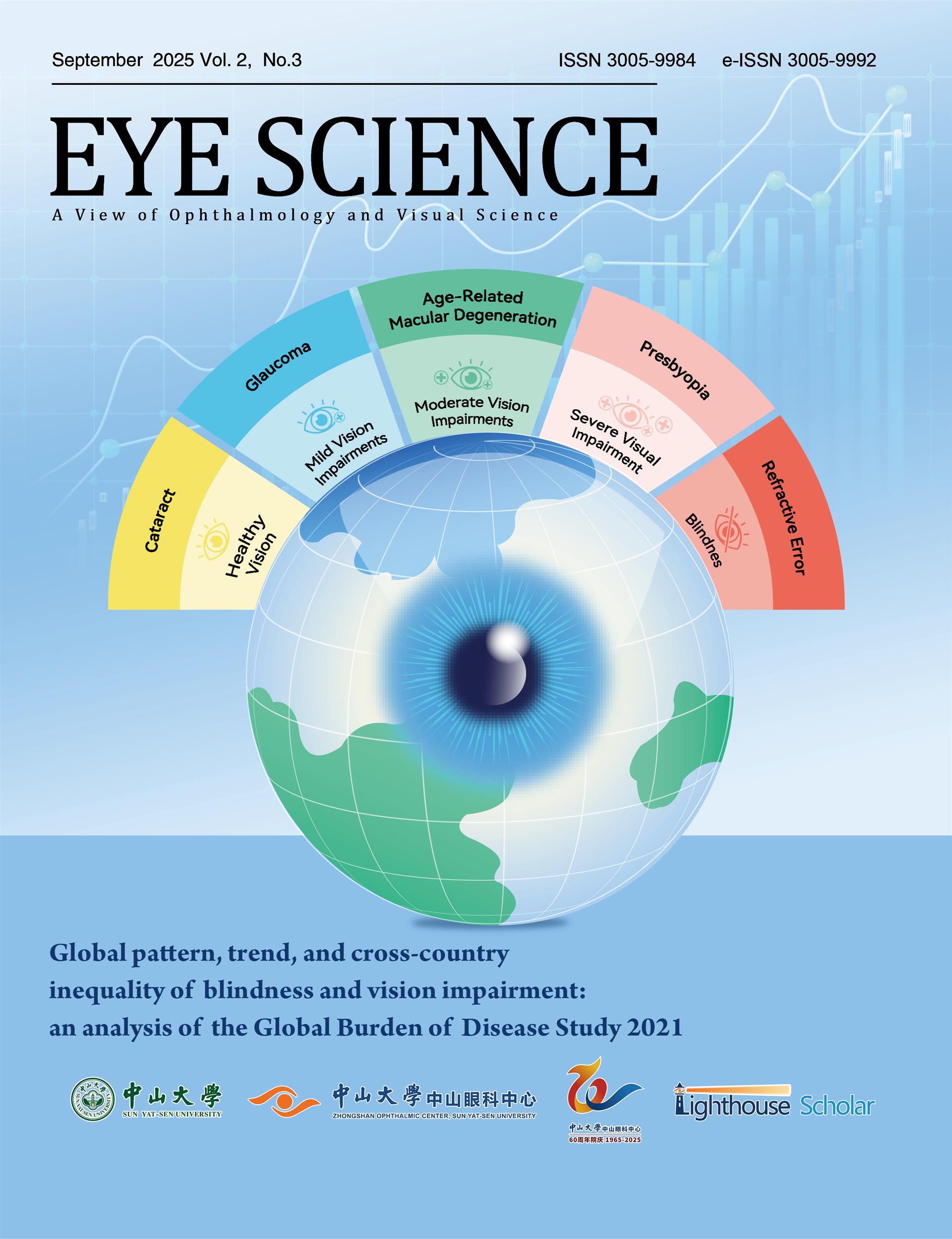

Globally, it’s estimated that at least 1 billion people have a near and/or distance vision impairment that could have been prevented or is yet to be addressed. The burden of unaddressed vision impairment and blindness is estimated to be four times higher in low and intermediate-resource settings than in high-income settings [1].

The number of people with non-communicable eye conditions is expected to surge in the coming years due to demographic, behavioural and lifestyle trends. Currently, an estimated 94 million people have a vision impairment or blindness that could be corrected through access to cataract surgery [2], while at least 826 million people have distance and/or near vision impairment that could be addressed with an appropriate pair of spectacles [2,3]. These figures are projected to increase, since presbyopia and cataract development are part of the ageing process, while growing evidence suggests that projected increases in myopia in the younger population will be driven largely by lifestyle-related risk factors. Increases are also expected in the number of people with noncommunicable chronic eye conditions, such as glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and complications of myopia. These conditions require a comprehensive range of interventions for their management, as well as long-term care, and these will have a profound impact on an already strained health system and eye care workforce [1].

Key challenges in expanding access to quality eye care services in low and intermediate-resource settings include, but are not limited to: (i) low population awareness and demand for eye care services; (ii) shortage and unequal distribution of the eye care workforce; (iii) high costs of accessing services; and (iv) the ability to provide services for underserved populations and outside urban areas [1].

SETTING THE NEW GLOBAL EYE CARE AGENDA

It is clear that new strategies are needed to address the current and projected eye care needs. The strategic recommendations outlined in World Health Organization’s (WHO's) first-ever World report on vision (2019) [1] were successful in providing the foundation for a ‘new’ eye care agenda that focuses on: (i) reorienting the model of care to strengthen eye care within primary care; (ii) improving coordination of services within and across sectors and related health programmes; and (iii) integrating eye care into wider health plans and policies.

Significant progress has been made in the last 5 years to facilitate more effective integration of these recommendations, particularly in low- and middle-income settings, through a series of global political commitments, including:

(i)Resolution WHA73.4 on “Integrated people-centred eye care, including preventable vision impairment and blindness” (2020) that endorses the recommendations of the World report on vision [4];

(ii)Resolution WHA74(12) endorsing the two global eye care targets for 2030 (2021), specifically a 30-percentage point increase in effective cataract surgery coverage (eCSC) and a 40-percentage point increase in effective refractive error coverage (eREC). These indicators serve as tracer indicators to monitor how actions and investments are delivering on the goal of improving eye health outcomes, and contributing to the advancement of universal health coverage [5];

(iii)United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolution on vision, A/75/L.108, "Vision for Everyone: accelerating action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals" (2021) that recognizes that improving eye care services and preventing vision impairment are particularly relevant to achieving many Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including those related to reducing poverty and improving workplace productivity, education, and equity [6];

(iv)Resolution WHA78.7 on “Primary prevention and integrated care for sensory impairments including vision impairment and hearing loss, across the life course” (2025), which promotes an integrated approach for systematic vision and hearing screening and early interventions services within relevant health programmes and sectors, health benefit packages and health information systems [7].

SUPPORTING COUNTRIES TO IMPLEMENT GLOBAL STRATEGIES: WHO’S TOOLS AND INITIATIVES

1. Eye care in health systems: guide for action: In collaboration with over 300 experts across all regions, WHO developed the Eye care in health systems: guide for action that provides practical, step-by-step support to countries in the planning and implementation of comprehensive eye care services [8]. It does so by stepping countries through a four phased cycle that includes (i) analysing the eye care situation of the country [9]; (ii) developing an eye care strategic plan and monitoring framework [10]; (iii) developing and implementing an eye care operational plan [11,12]; and (iv) evaluating and modifying the operation plan. WHO has supported approximately 40 countries to strengthen eye care within their health systems using one or more of the ‘guide for action’ tools. This included the translation and launch of the ‘guide for action’ in China in 2023, in partnership with WHO Collaborating Centre for Eye Care and Vision; the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University.

2. WHO SPECS 2030 initiative: In May 2024, WHO launched the SPECS 2030 initiative [13] to support Member States to sustainably reach the more than 800 million people in need of refractive error services. The SPECS 2030 initiative calls for coordinated action across 5 key pillars:

· improve access to refractive Services;

· build capacity of Personnel to provide refractive services;

· improve population Education;

· reduce the Cost of refractive error services, and

· strengthen Surveillance and research.

Through this global initiative, and in collaboration with experts and other stakeholders all over the world, WHO has (i) developed the necessary normative guidance for refractive error [14–16]; (ii) commenced convening of key private sector actors to seek meaningful contributions to scaling up refractive error services; and (iii) established a WHO-hosted Network that currently has 43 member organizations from the eye care and refractive error sector, UN Agencies and philanthropic organizations [17]. Importantly, since its launch, there has been strong country demand for the initiative, with 17 countries already committing to implement national or sub-national SPECS 2030 initiatives.

3. Strengthening monitoring and surveillance: To support monitoring of progress towards achieving the 2030 global eye care targets, WHO actively works with academic institutions to periodically generate estimates on eCSC and eREC [18,19]. Additional activities to expand the quality and quantity of data for these global indicators include the integration within the WHO NCD STEPS survey [20,21] and within tropical data surveillance, as well as the upcoming launch and targeted implementation of a new WHO Sensory Impairment Interventions Survey (SENSIIS): Study Manual in 2025. Furthermore, WHO has developed a range of technical resources in order to support countries to strengthen health information systems for eye care. That is, a comprehensive set of indicators, assessing health system performance and health status, is provided in the Eye care indicator menu [22] and in the Routine health information systems toolkit for sensory functions [23], which includes a District Health Information Software 2 digital package.

CONCLUSION

While current data from the field continues to paint the picture of substantial inequities in access to eye care, there is sound justification for optimism. Significant momentum has been built in recent years, including (i) a strengthened body of evidence and data for advocacy and action; (ii) an increased availability of technical guidance to support implementation of comprehensive eye care services within countries; (iii) a united and growing stakeholder group (e.g., non-government organizations, academic institutions etc.); and (iv) a growing country demand for action on eye care. It is now time to capitalize on the momentum and scale up actions to ensure that all people can receive quality eye care services.

Correction notice

None

Acknowledgements

None

Author Contributions

(I) Conception and design: Stuart Keel

(II) (II) Administrative support: Not applicable

(III) Provision of study materials or patients: Not applicable

(IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors

(V) Data analysis and interpretation: Not applicable

(VI) Manuscript writing: All authors

(VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Funding

None

Conflict of Interests

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors have declared in the completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form.

Patient consent for publication

None

Ethics approval and consent to participate

None

Data availability statement

None

Open access

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license).